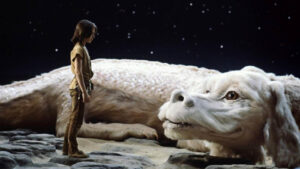

Close Encounters of the Third Kind. Photo Credit: Columbia Pictures

In the annals of science fiction cinema, few films have left as indelible a mark as Steven Spielberg’s “Close Encounters of the Third Kind.” Released in 1977, this cinematic masterpiece dared to ask the question: “What if aliens came to Earth and communicated through an intergalactic version of ‘Simon Says’?”

At its core, “Close Encounters” is the story of Roy Neary, an everyday Joe whose life takes a sharp turn into the extraordinary when he encounters a UFO. Played by Richard Dreyfuss at his most wonderfully unhinged, Roy goes from being a regular suburban dad to a mashed-potato sculptor with a penchant for ripping up his front yard faster than you can say “We are not alone.” It’s like watching a midlife crisis on steroids, with added alien interference.

The film opens with a series of mysterious events that would have Fox Mulder salivating. Lost planes suddenly reappear, household appliances go haywire, and a little boy is abducted by what can only be described as the universe’s most elaborate Christmas light display. Meanwhile, a group of scientists, led by a wild-haired Frenchman named Lacombe (François Truffaut), scurry around the globe collecting clues like they’re on an extraterrestrial scavenger hunt.

Played by Richard Dreyfuss at his most wonderfully unhinged, Roy goes from being a regular suburban dad to a mashed-potato sculptor with a penchant for ripping up his front yard faster than you can say “We are not alone.”

But the real magic happens when Roy has his close encounter. Spielberg, in a stroke of genius, decides that the best way for advanced alien life forms to introduce themselves is by nearly running our protagonist off the road and giving him a cosmic sunburn. It’s like the universe’s worst meet-cute, but it sets Roy on a path of obsession that would make Captain Ahab say, “Dude, maybe chill a bit?”

As Roy’s obsession grows, so does his family’s concern. His wife watches in horror as he turns their living room into an alien-inspired art installation, complete with a mountain made from garden soil and garbage. It’s a poignant portrayal of a man grappling with an experience he can’t explain, or it’s a cautionary tale about the dangers of watching too much “Art Attack” – you decide.

Meanwhile, across town, Jillian Guiler (Melinda Dillon) is dealing with her own close encounter aftermath. Her son Barry has been taken by the aliens, presumably because they needed a human child to explain how Speak & Spells work. Jillian and Roy eventually cross paths, bonded by their shared experiences and their mutual ability to draw the same lumpy mountain over and over again.

The mountain, as it turns out, is Devils Tower in Wyoming, which apparently is the alien equivalent of a hip downtown coffee shop – the perfect spot for a first contact meet-up. As Roy and Jillian make their way to Wyoming, the government is busy setting up for the big event. They evacuate the area under the guise of a nerve gas spill, because nothing says “nothing to see here” quite like the threat of chemical warfare.

The film builds to its spectacular climax at Devils Tower, where Spielberg pulls out all the stops. The mother ship arrives in a dazzling display of lights and sound that makes the average EDM concert look like a kids’ birthday party. The aliens, it seems, have a flair for the dramatic that would put Broadway to shame.

The real kicker comes when we discover how these advanced beings have chosen to communicate: through a five-note musical phrase. That’s right, all our technological advancements, all our complex languages, and the key to interstellar communication turns out to be a jingle that wouldn’t be out of place in a breakfast cereal commercial. It’s like finding out that the secret to world peace is hidden in the Macarena.

As the aliens finally emerge from their ship, we’re treated to a visual that has become iconic in sci-fi cinema: the willowy, big-headed beings that have launched a thousand conspiracy theories and questionable History Channel documentaries. They return the humans they’ve borrowed (apparently, the aliens have a better return policy than most libraries), and then, in a twist that would have child services up in arms, they invite Roy to join them on their cosmic journey.

Roy, having thoroughly trashed his lawn and his marriage, decides that yes, gallivanting off with a bunch of aliens he’s just met is definitely the sensible choice here. As he boards the ship, we’re left to ponder the profound questions the film raises: Are we alone in the universe? What would first contact really be like? And most importantly, did Roy remember to pack a toothbrush for his interstellar road trip?

“Close Encounters of the Third Kind” stands as a testament to Spielberg’s unparalleled ability to blend the ordinary with the extraordinary. It’s a film that takes the concept of alien contact and grounds it in the mundane realities of suburban America, creating a contrast that’s both thought-provoking and occasionally hilarious. It suggests that when the aliens do come, they might just as likely encounter us while we’re taking out the trash as when we’re at our most dignified.

The film’s legacy is undeniable. It set the standard for how UFOs and alien encounters would be portrayed in cinema for decades to come. It gave us the iconic five-note sequence that’s become shorthand for “Hey, aliens, we come in peace!” And it forever changed how we look at mashed potatoes and shaving cream.

In the end, “Close Encounters of the Third Kind” is more than just a sci-fi classic. It’s a meditation on humanity’s place in the cosmos, a celebration of wonder and curiosity, and a reminder that sometimes, the path to the stars might just start in your own backyard – assuming you haven’t dug it up to build a model mountain, that is.